Research

1. Ensemble coding for fast vision–action interactions

2. Joint visuomotor movements in real world settings: Working with human or robot co-workers for common goals

3. Visuomotor abilities in children

4. Multimodal neuroimaging for a better understanding of temporal and spatial properties of brain dynamics

(1) Ensemble coding for fast vision–action interactions

You never see the same world twice: Visual inputs from the world constantly change, and our actions are continually in motion (at least our eyes) even when trying to remain still. Everytime we open our eyes, our brain receives a barrage of new information from the complex and cluttered visual environment. Our brain manages this surprisingly well; It condenses and reconstructs images by grouping parts (e.g., objects) into meaningful sets (e.g., ensembles), relying on similarity, redundancy, or structural regularity in the images. Ensemble coding operates to dilute high-level descriptions into "summary representations."

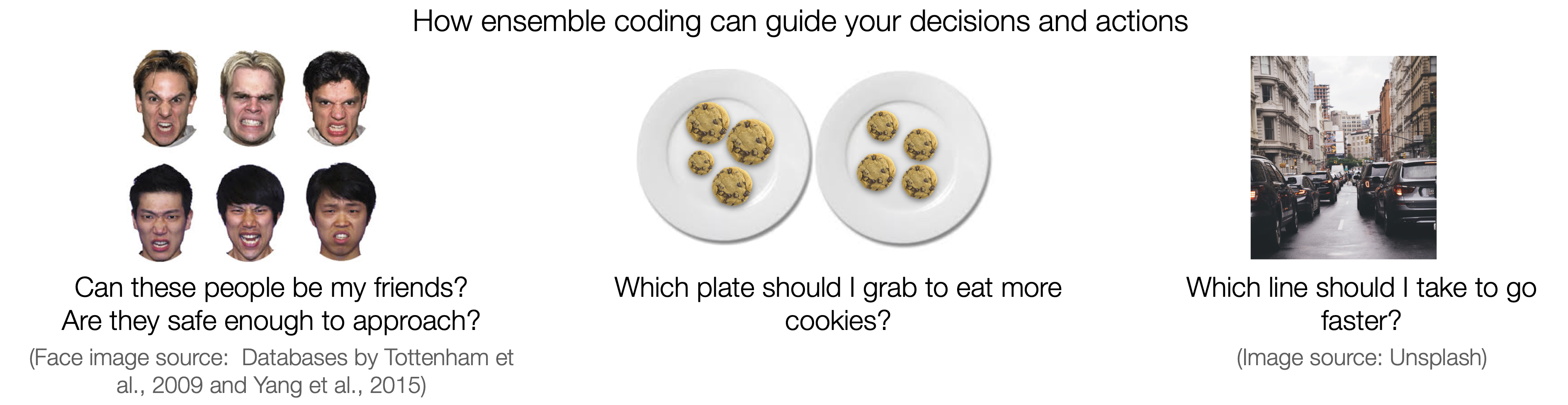

Ensemble coding is an excellent example of adaptive visual processes the brain uses to lighten its cognitive workload required for processing and remembering all details of images. Studies have shown that people are incredibly adept at perceiving ensembles made of various features, including size, motion, orientation, and facial emotions or identities. Particularly, ensemble coding's utility is in its processing speed, instantly creating coherent snapshots of the ever-changing visual world. It can then initiate instant action commands based on snap judgments about the current environment: e.g., Should I move away from those grumpy people surrounding me? Which plate to grab to get more cookies before someone else takes it?

We are currently studying how different parts of the brain work during this dynamic processes where visual ensembles are perceived and guide our movements for interacting with and navigating the world.

*This work is funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada and the National Research Foundation of Korea.

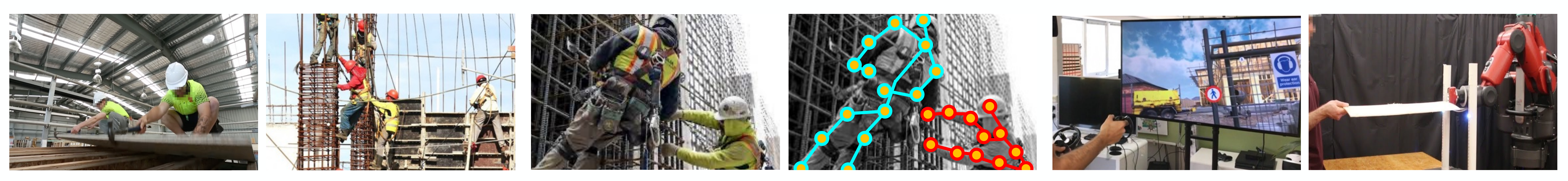

(2) Joint visuomotor movements in real-world settings: Working with human or robot co-workers for common action goals in construction sites

We often make goal-directed movements, not by ourselves, but in collaboration with others, such as lifting and moving a heavy object or hanging a big picture frame on the wall. We study how the human brain works to mediate interactive and collaborative visuomotor movements. For joint movements, not all actions are performed by one person; a series of complex movements is often partitioned into discrete and simpler segments, then different portions are assigned to each person. From one person's perspective, their individual actions wouldn't make up a meaningful set of continuous movements: Instead, there should be discontinuity, pauses, or rushes to temporally coordinate different actions and synchronize work dynamics with others. For joint movements, therefore, they must be able to understand others' minds, action intentions, goals, and current progress, relying on cognitive, behavioural, emotional, and linguistic cues.

Performing joint movements is integral to dynamic workflows in many industrial settings, such as construction and maintenance sites. Successfully planning and executing joint movements in the correct order and at the right time is vital for workers' safety and product quality. As a part of a collaborative group with researchers from Civil Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Biomedical Engineering, and Computer Science, we are currently exploring cognitive, behavioural, and neural processes during successful and unsuccessful collaborative visuomotor movements in the real-world scenarios of construction sites, created by virtual reality and mobile labs equipped with wearable sensing devices. As a neuroscience research team, we lead studies on human abilities and strategies to assess action intentions, motor capability, and emotional and cognitive states of other co-workers and then, most importantly, to adjust and modify their own action plans and execution accordingly in real-time. We use visuomotor tasks made of common and essential functional modules for achieving manipulation goals in construction sites, including reaching, grasping, lifting, rotating, pulling, etc. We examine the brain signals, behavioural performance and 3D movements, and biophysiological measures in human construction workers during these collaborative visuomotor tasks.

Now that the construction industry is becoming more futuristic (!!), with WALL-E-like robotic workers assisting human workers in many dexterous, physically demanding, and dangerous tasks, we also study human-robot collaborations during the same visuomotor movements in virtual construction settings that are distracting, cluttered, and busy. We generate multimodality data from human construction workers, measuring cognitive/emotional states (e.g., attentional focus or distraction, anxiety, confidence level, etc.) and behaviours (e.g., common patterns observed immediately before human lapses and errors which can sometimes be fatal, such as falling or dropping). These data are processed so that they serve as useful inputs for controlling policies of human-centred construction robots being developed by our research collaborators in engineering departments. We hope this interdisciplinary research project will improve robot construction workers' abilities to read and respond to how human co-workers learn, move, feel, and make decisions on site and enhance training programs and task structures for human co-workers, making working dynamics between robot-human pairs safer and less demanding.

*This work is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada.

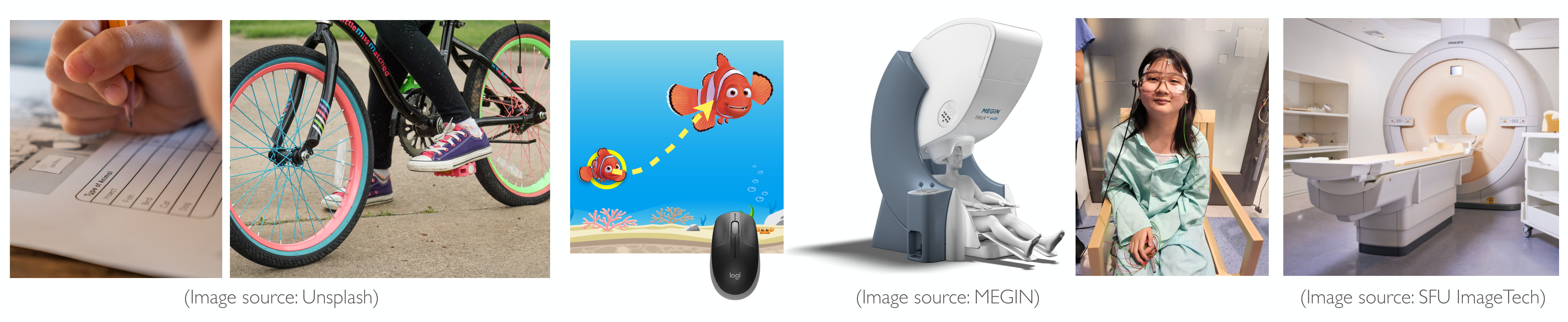

(3) Visuomotor abilities in children: development of vision and action links and impacts of early neurodevelopmental disorders

Visuomotor experiences during childhood play a significant role in wiring the brain and shaping lifetime interactions with the world. Learning to coordinate our eyes and body's (especially our hands and feet) by adjusting movements in response to visual feedback is an important developmental milestone for children to acquire gross and fine motor skills, such as writing, tying shoe laces, walking, and artistic or athletic activities. We study the developmental patterns of such vision and action links in children of a wide age range, from 5 to 18 years old, to better understand how early visuomotor experiences impact the way their developing brains wire and create neural connections to build "functional networks.”

Using neuroimaging devices that are non-invasive and suitable for testing children (mainly magnetoencephalography [MEG], but we use some other devices too!), we measure detailed time series of brain activities and the brain's rhythmic patterns. These measurements provide insight into how vision and action links unfold over time across different brain regions in young children with typical development or with neurodevelopment disorders. Our animated, aquarium-themed tasks are designed to be entertaining and easy enough for children to perform. The task allows us to record a rich set of continuous hand movement data over time while the children's brain activities are recorded with MEG. Combining the hand movement data and the brain time-course recordings, we are currently exploring how and when the visual and motor systems communicate during successful versus unsuccessful movements and how excitatory and inhibitory connections among different brain regions coordinate goal-directed actions.

Because children's brains are still plastic, disruption in one function (e.g., vision) will likely have far-reaching and lasting consequences on the ways that the brain's functional specialization is shaped and established in the long run. This motivates our recent projects on visuomotor skill learning in children who have reduced vision due to a neurodevelopment disorder called amblyopia (also called lazy eye) early in life. We study how reduced vision during early childhood is associated with a cascade of impacts on visuomotor abilities and subsequent changes in a range of brain functions, which must be acquired and matured during this critical period for brain and behaviour development.

*This work is funded by the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Brain, Behaviour, and Development Theme and UBC Health.

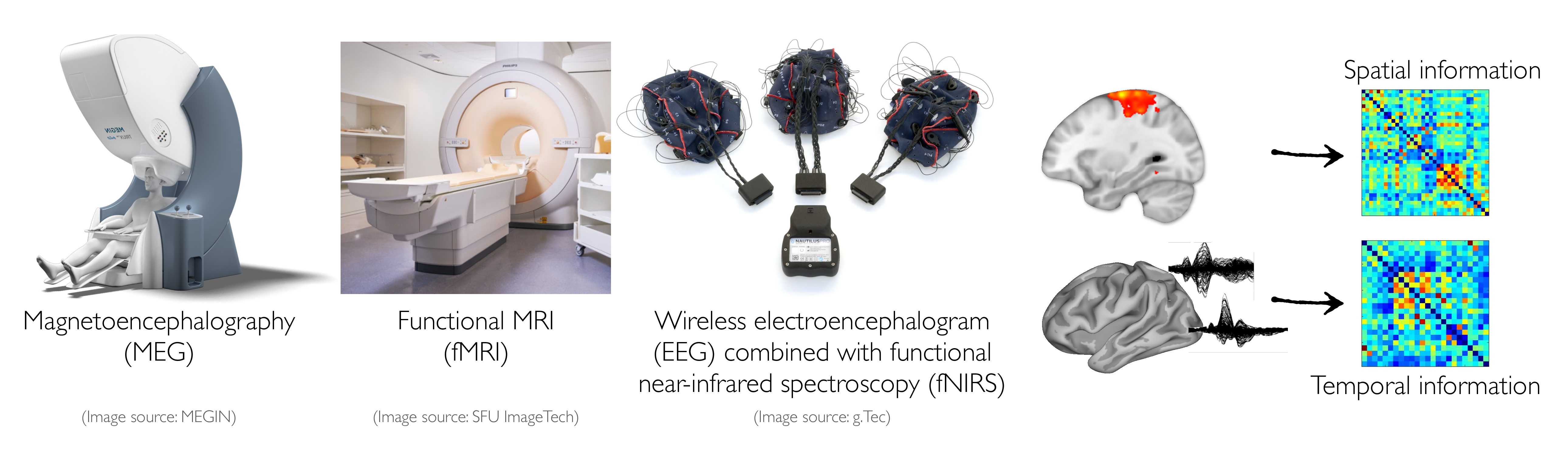

(4) Multimodal neuroimaging for a better understanding of temporal and spatial properties of brain dynamics during visually-guided movements

Brain recording and functional neuroimaging techniques (e.g., magnetoencephalography [MEG] and functional MRI [fMRI]) are powerful and noninvasive tools to examine typical and atypical brain function and development, informing researchers of neural mechanisms underlying behaviours and possible neural anomalies due to disorders. However, none of these methods directly measure neuroelectrical or neurochemical processes mediating brain function. Brain "activity" must be inferred from other metrics such as magnetic fields (e.g., MEG) or hemodynamics (e.g., fMRI). To overcome this limitation, multimodal approaches combining neuroimaging devices such as fMRI and MEG can be useful, providing complementary information. fMRI can characterize brain activity with sub-millimetre spatial resolution, but has limited temporal resolution; MEG can characterize neural activity on the millisecond timescale at which the brain operates but with a limited spatial resolution. Combining MEG and fMRI has great potential for providing insights into the dynamic brain function underlying behaviours and neurocognitive biomarkers of pathological brain changes.

For the fusion of MEG and fMRI to be useful in obtaining high spatial and temporal resolution, the two signals should reflect the same underlying neural events. Previous work has suggested that neuromagnetic (MEG) and hemodynamic (fMRI) signals originate from post-synaptic currents and tend to correlate with each other. Our previous work also provided evidence for similar, overlapping patterns of whole-brain MEG and fMRI activations in healthy adults during face perception. We are currently exploring robust approaches to combining time-course MEG and fMRI data from the same participants who perform the same tasks in the MEG and MRI scanners in separate sessions. We hope that this work will provide a comprehensive understanding of when and where neural activity occurs during cognitive and motor tasks.

For mobile studies using our recent virtual reality setup, we alternatively use electroencephalography (EEG; better temporal resolution) combined with functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS; better spatial resolution), instead of huge MEG (better temporal resolution) and fMRI (better spatial resolution) scanners, so that participants can make movements with more freedom in less restricted settings.

*This work is funded by the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.